In a lay-by by the side of the B6318 in rural Northumberland there stands an oak cross, which was installed in the 1930s. What is this monument doing in a roadside lay-by, just east of the site of Turret 25B on Hadrian’s Wall, one of the series of turrets and milecastles that protected the wild north-west frontier of the Roman Empire and stretched 73 miles from coast to coast?

Although there is little of the Roman Wall readily visible from the cross, the straightness of the road provides an echo of the wall’s former presence and the visible archaeology in the vicinity an inkling of how it must have dominated the Roman and early-medieval landscape. Several centuries after the Romans had left Britain, the venerable Bede wrote in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People of ‘a famous wall, which is still to be seen… 8 feet wide and 12 feet high, running in a straight line from east to west, as is plain for all to see even to this day.’

And later in his Ecclesiastical History Bede mentions the wall again when describing this place, Heavenfield, which is associated with the victory of Oswald of Northumbria over Cadwallon, king of the Britons. Bede describes Heavenfield as lying ‘close to the wall with which the Romans once girded the whole of Britain from sea to sea, to keep off the attacks of the barbarians’. With this topographical reference Oswald is given an aura of civilised Romanitas while the vanquished ruler of the Britons takes the role of unruly barbarian, albeit the geography of the wall has been flipped on its head – now it defends a northern king from barbarous forces approaching from the south.

Oswald had been born into the Bernician royal family and was exiled amongst the Irish in his early teens after his maternal uncle Edwin had killed his father. Oswald converted to Christianity while in exile – he was probably baptised at Iona – and on his return from exile won his famous victory against Cadwallon and became king of Northumbria, subsequently uniting Bernicia with Deira. Bede says that the king of the Britons was killed at a place called Denisesburn, thought to be close to Devil’s Water, some 8 or 9 miles south of Heavenfield – the actual battle was probably fought a few miles from Heavenfield itself and presumably Oswald’s forces then chased down the feeling Britons.

Bede is much more interested, however, in Heavenfield than in Denisesburn. He writes that the place was known as Heavenfield even before Oswald’s victory and that this was an omen: ‘it signified that a heavenly sign was to be erected there, a heavenly victory won, and that heavenly miracles were to take place there’. The heavenly sign was a wooden cross that Oswald had set up before the battle. Oswald is said to have held the cross with his own hands while his soldiers dug a hole, in which he then placed the cross while the soldiers filled it with earth. Oswald then exhorted his troops to kneel before it and pray. This they did and then, Bede tells us, they ‘advanced against the enemy just as dawn was breaking, and gained the victory that their faith merited’. Through the symbol of the cross Oswald becomes a kind of Northumbrian Constantine, with his victory at Heavenfield echoing Constantine’s at the Milvian Bridge, which marked the beginning of Constantine’s conversion and of Christianity becoming the dominant religion of the Roman Empire.

The wooden Cross quickly became a place of veneration and was associated with miracles. Bede said that even in his day people would cut splinters from the cross and place them in water – the water then having the power to cure sick men and animals when drunk by them or sprinkled on them. Bede tells us about one miracle in some detail. This concerns a monk, still living when Bede wrote, from nearby Hexham. Bothelm, as he was called, had slipped on some ice while walking incautiously and had broken his arm. He was in severe pain. Hearing that one of his brothers intended to visit Heavenfield he asked for a splinter of the cross to be brought back to the monastery for him. Instead of cutting a splinter, the brother removed some old moss from the surface of the cross. On his return to the monastery, he gave the moss to Bothelm, who secreted it about his person and then forgot all about it, going to bed with it still there. He awoke in the night feeling a cold sensation and discovered that his arm and hand were healed.

It is no surprise that a monk of Hexham should be the beneficiary of a miracle of Oswald’s cross, because Hexham Abbey played a significant role in protecting and promoting the site from the earliest days of the abbey’s existence. Hexham was founded about 4 decades after Oswald’s victory at Heavenfield by St Wilfrid. It quickly became customary for the monks to spend the vigil of Oswald’s feast day at Heavenfield, singing many psalms of praise for the benefit of the Northumbrian king’s soul. On the morning of his feast on 5 August they then offered up the holy sacrifice and oblation on Oswald’s behalf. This custom had become so popular, that by the time Bede wrote a small church had been constructed on the site. This building was the forerunner to the little church dedicated to St Oswald at the top of the hill, which now stands in a churchyard separated from the surrounding field by a drystone wall.

No trace of the first building remains above ground. It was replaced in the Norman period. At some point the site also became a hermitage. In the registers of Thomas Corbridge (Archbishop of York from 1299-1304) there is a document in which the archbishop assents to the Prior of Hexham’s request that a certain Simon of Meynill be allowed to live the life of a hermit along with a Brother John at St. Oswald’s near Hexham.

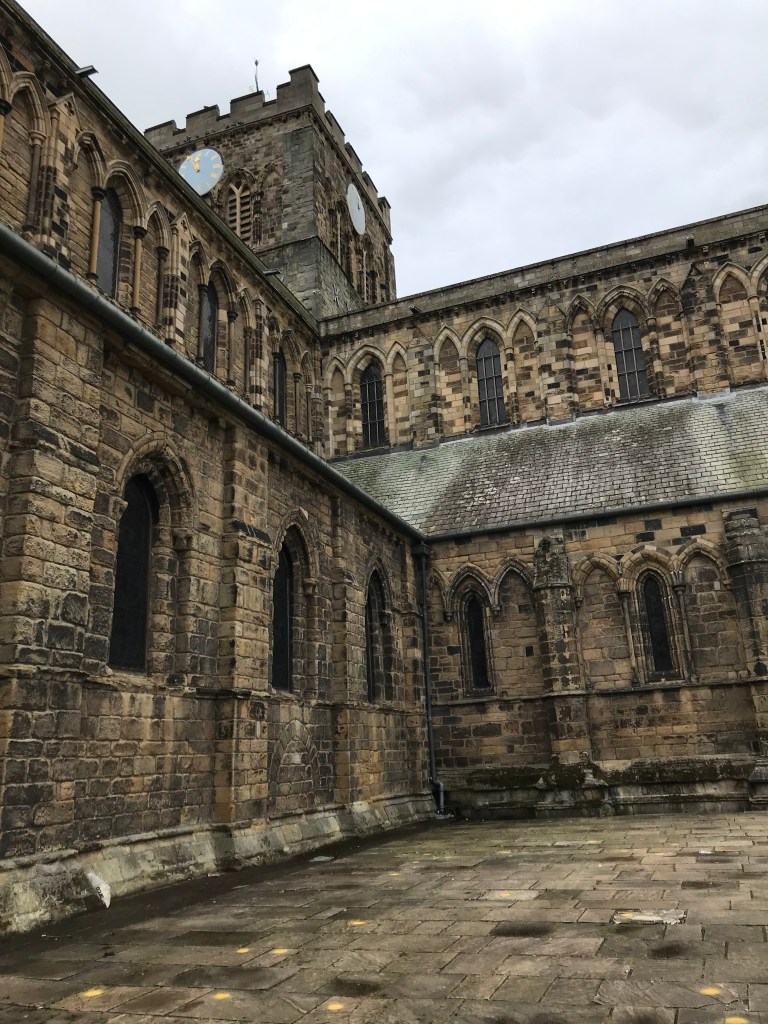

The present church building dates from 1817 and the fragment of dog tooth ornament inside the church on the north wall is all that remains visible of the second Norman church. The church comprises a chancel divided at the west end into a vestry, the rest being the body of the church. The roof is adorned with a simple belfry and the interior is of limewashed stone without any plaster. The church has never been connected to mains electricity, gas or water and is lit by a combination of gas lighting and candles. Although Victorian, the simplicity of the church and its setting in the rugged Northumbrian landscape alongside the course of Hadrian’s Wall, provides a powerful sense of connection to the early-medieval past that the church commemorates.

Well worth a visit. Did so myself last year.

LikeLiked by 1 person