Sara Ameri Mahabadi

Some time in the 13th century, a warrior martyr of the 3rd century suddenly acquired a new significance as protector against plagues. St. Sebastian was a Roman soldier who converted to Christianity, was shot with multiple arrows, which he miraculously survived, and was then clubbed to death and thrown into the city sewage. For the next 10 centuries, he remained an important but localized saint in Rome mostly known for his Christ-like resurrection. In the mid-13th century, however, Jacobus de Voragine composed one of the most famous lives of saints in the European Middle Ages, Legenda aurea, which includes the first substantial vita of St. Sebastian. This account emphasized the connection of St. Sebastian to the plague.

For the next couple of centuries, the iconography of St. Sebastian as a plague saint spread across Europe, and the arrows piercing his bodies became the tell-tale sign of the pestilential buboes.

In 1484, William Caxton printed the first English translation of the Legenda as The Golden Legend. The success and popularity of this edition is attested to by its 10 reprints between 1484 and 1527.

These editions are very similar though not identical. The preferences of the printers and the changing audience affected the shape, size, order, and layout of the books. Here, I will focus on one varying aspect between the1484 and 1504 editions, that is, the identifiable figure of St. Sebastian in the woodcuts.

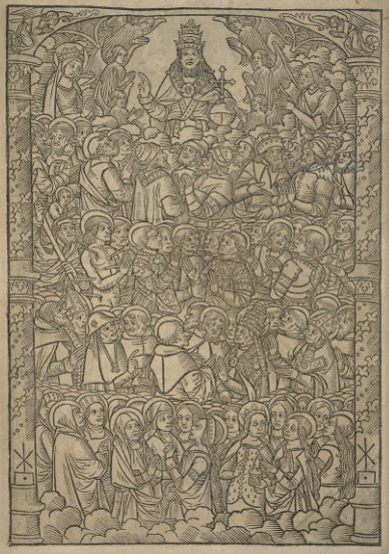

The frontispiece of Caxton’s first edition (1484) shows the Trinity above a host of biblical figures, lay and ecclesiastical saints, both female and male. It was an exercise both in advertising the new translation and promoting certain national sentiments, as evidenced by the distinct representation of several English saints such as St. Thomas Becket and St. Ælfheah of Canterbury.

There is, however, no figure that can be visibly associated with St Sebastian and his iconography of arrows. The only figure with an arrow (top row, fourth figure from the left) is decidedly not St. Sebastian but St. Edmund, the English king of East Anglia and the original patron saint of England. He is marked by his regal attire, a feature that has no association with St. Sebastian. Moreover, the chapter dedicated to St. Edmund in Caxton’s edition begins with a similar illustration of him holding an arrow and wearing a crown while St. Sebastian’s life is not among the chapters with an illustration. This emphasis through illustrations on an English saint and king is in line with Caxton’s national and political allegiances.

This frontispiece was reproduced exactly in the following editions of the book in the 15th century (1493 and 1498) by Caxton’s fellow printer in London, Wynkyn de Worde. However, a change occurred in the woodcut in the first edition of the 16th century. Julian Notary, a native of Brittany and a third active printer in 15th and 16th century London, published a much smaller edition of the Legend in 1504. The frontispiece of this volume is subtly different from Caxton’s. God is depicted not as the Trinity but a papal figure, and the saints below are frustratingly unidentifiable. Except St. Christopher carrying the child Jesus, St. Sebastian, and possibly St. Barbara, the rest are a motely host of kings, soldiers, popes and lay and monastic men and women. Even among the recognizable figures, the easy and instantaneous identification of St. Sebastian is remarkable.

In this illustration, St. Sebastian holds roughly the same, center-left position as St. Edmund did in Caxton’s 1484 edition. Additionally, St. Sebastian’s chapter begins with an illustration this time while St. Edmund’s has shrunk in size and distinctiveness. In Notary’s edition, then, one arrow saint has effectively replaced another.

What may be the reason behind this? And what are its effects?

In 1500, a major outbreak of the plague hit London after 20 years of plague-free peace—the longest interval between outbreaks in 100 years. This renewed the demand for a patron saint against the plague, a demand to which Notary responded well. As Judy Ann Ford has observed, Notary’s edition was much cheaper, easier to carry, more difficult to read, and more extensively illustrated than Caxton’s.[1] It was tailored to the daily, non-expert consumption of average readers who had just survived a vicious attack of the pestilence and would have certainly welcome the central depiction of a plague saint with a rising reputation. Notary’s non-English background could have been a further motivation in replacing a thoroughly English saint with a popular European one. This move placed the translation within a more international network and aligned the audience to a broader textual and visual culture. In this way, St Sebastian appeared not only as a much-needed, individual protector against the pestilence but also a shared icon of global disaster.

Sara Ameri is a PhD Candidate at the University of Toronto, Department of English. Her research focuses on the medieval plague and its function and representation in late medieval devotional writings. She is also a research assistant in the Old Books New Science and Reading Muslims projects at the University of Toronto, with interest in the global Middle Ages and critical theory.

[1] Ford, English Readers of Catholic Saints: The Printing History of William Caxton’s Golden Legend. (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2020). https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429296895.